FM Dar Visit To Dhaka Ushers In New Pak-BD Trust Ties

In diplomacy, certain visits go beyond protocol and set new directions. Pakistan’s Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, Ishaq Dar, recently travelled to Bangladesh in such a spirit—seeking to reset relations and adapt them to South Asia’s shifting strategic environment.

The story of Pakistan–Bangladesh ties is one scarred by history. The rupture of 1971, when East Pakistan seceded to form an independent state, left behind deep mistrust. Although Pakistan formally recognized Bangladesh during the Lahore Islamic Summit of 1974, confidence never fully returned. Over the decades, successive Pakistani regimes repeatedly attempted to build bridges through delegations, trade contacts, and cultural exchanges. Yet, on the Bangladeshi side, efforts were far less visible. In particular, under Sheikh Hasina’s long rule, Pakistan was often confronted with harsh rhetoric and little willingness to reconcile, which deepened the sense of estrangement.

India’s influence has always loomed large over this equation. New Delhi not only shaped the events of 1971 but, in subsequent decades, consolidated its grip through political, economic, and defence partnerships with Dhaka. Hasina’s tenure brought even closer alignment with India, while anti-Pakistan narratives often gained ground. Yet the strategic landscape is shifting: China’s growing footprint, Gulf investment, and the involvement of countries like Turkey and Malaysia are reshaping South Asia’s dynamics. Within this altered environment, rebuilding Pakistan–Bangladesh ties has become a strategic necessity rather than a mere diplomatic option.

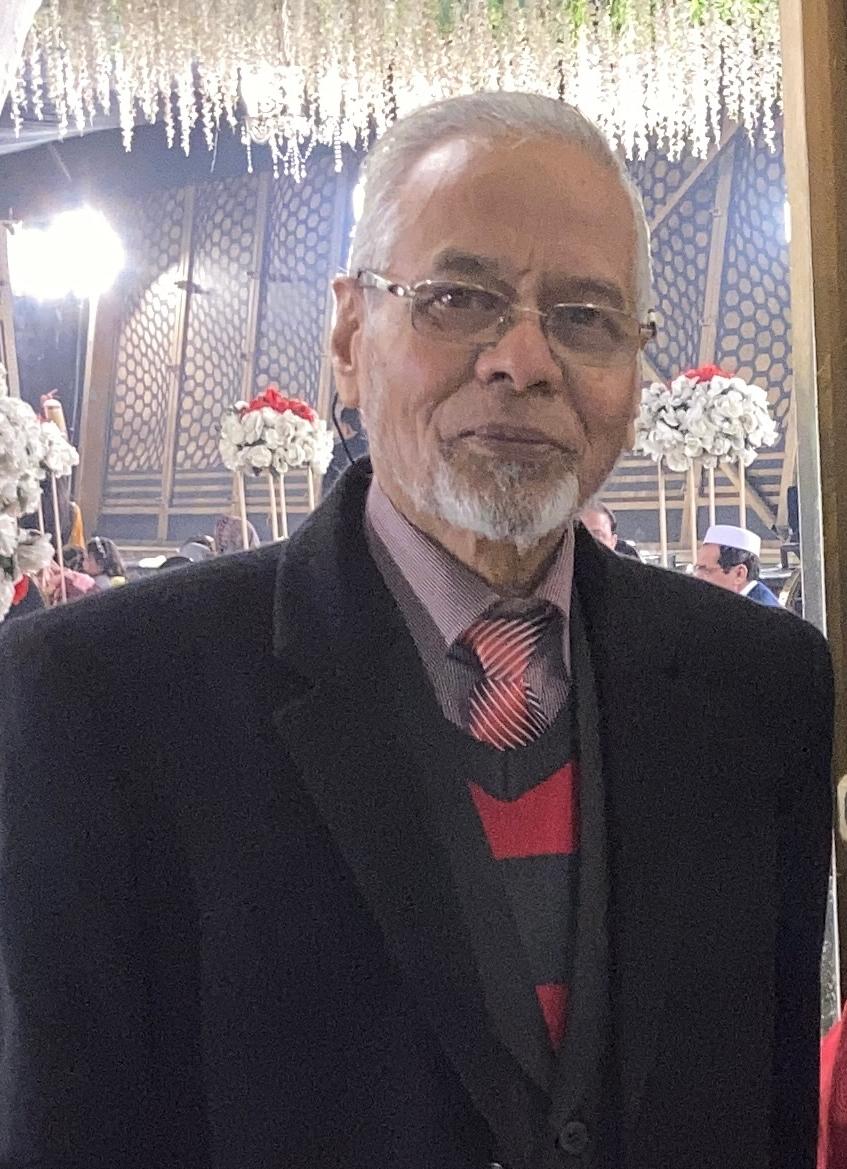

Among Pakistan’s leadership, there has long been recognition of the need for reconciliation and closer ties with Dhaka. Ishaq Dar’s present visit, reflecting the policy vision of Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, carries this approach forward. Nawaz Sharif consistently supported initiatives to expand trade and cultural linkages, believing they could heal old wounds. Dar’s message of goodwill is therefore in line with that same vision of nurturing relations between two sister nations, even when reciprocity was lacking in Dhaka.

The mission itself carried significance beyond symbolism. As Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, Dar entered Dhaka with a concrete agenda. He spoke of expanding trade and investment, broadening cooperation in education and culture, and leaving historical grievances behind. At present, bilateral trade stands below $1 billion—far beneath the potential of two large and dynamic economies. Raising it even to $5 billion could provide substantial benefits. Pakistan can offer textiles, pharmaceuticals, and agricultural products, while Bangladesh’s thriving garments industry could benefit from Pakistani cotton and yarn. Joint ventures and possible links to the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) could further energize this cooperation.

Beyond economics, cultural affinities remain a vital asset. Despite political estrangement, people-to-people connections run deep. Pakistani dramas and films enjoy popularity in Dhaka, while Bangladeshi music and cricket resonate with Pakistani audiences. Dar emphasized that educational exchanges, cultural programmes, and sports diplomacy could form more durable foundations for bilateral trust.

There are also opportunities on multilateral platforms. In organisations such as the OIC, SAARC, and Commonwealth, the two countries could support each other’s positions instead of working in isolation. Their respective ties with the Gulf—Bangladesh as a major supplier of manpower, Pakistan through its political and security partnerships—could be combined to unlock new opportunities in the Middle East.

The broader lesson of history suggests that reconciliation is always possible. The United States and Japan became partners despite the shadow of Hiroshima. East and West Germany overcame decades of division to reunify as Europe’s central power. European states, after two catastrophic wars, forged one of the strongest economic blocs in the world. Why then should Pakistan and Bangladesh remain hostage to past grievances? Once united as one country despite their geographical separation, they today account for nearly 400 million people—one of the largest segments of the Muslim world. Their unity could embody the Qur’anic injunction to hold fast together and Iqbal’s vision of Muslim solidarity.

If pursued with sincerity, renewed ties between Islamabad and Dhaka could generate not only economic dividends but also a sense of shared leadership within the Muslim world. Ishaq Dar’s Dhaka mission may well be remembered as the first step in that direction—an attempt to heal the scars of history and open a future of cooperation, strength, and shared prosperity.